Path Paved with Resilience

Baho Coffee owns and runs 10 washing stations across Rwanda, located in different coffee-growing regions with different quality potentials, and two others in Burundi. The company, which sells small-holder farmers’ coffee to clients around the world, has more than 100,000 members, including producers. It also partners with farmers in the Democratic Republic of the Congo to help them to understand and implement the best practices of coffee processing methods.

Founder Rusatira Emmanuel studied agricultural engineering, rural development and agribusiness studies in university. Upon graduation, he spent 12 years working at a multinational coffee exporter in Rwanda that has operations across the globe. He established Baho in 2017, driven by the passion to empower small-scale farmers in Rwanda who are marginalized despite producing delicious coffee.

We met Emmanuel for the first time at the World of Coffee 2022, a trade show held in Milan, Italy. He was radiating energy like the sun, shining light on everyone around him. It was only afterwards that we found out about his prowess as a coffee producer and a chapter of his life as dark as an abyss.

In Kinyarwanda, an official language of Rwanda, “baho” means “stay strong” and “never give up.” Using the word for his company’s name was a decision that’s intertwined with his past, one where he pulled himself out of the depths of despair. In an interview, Emmanuel told us what he wants to achieve through the coffee business.

Selling Rwanda with family

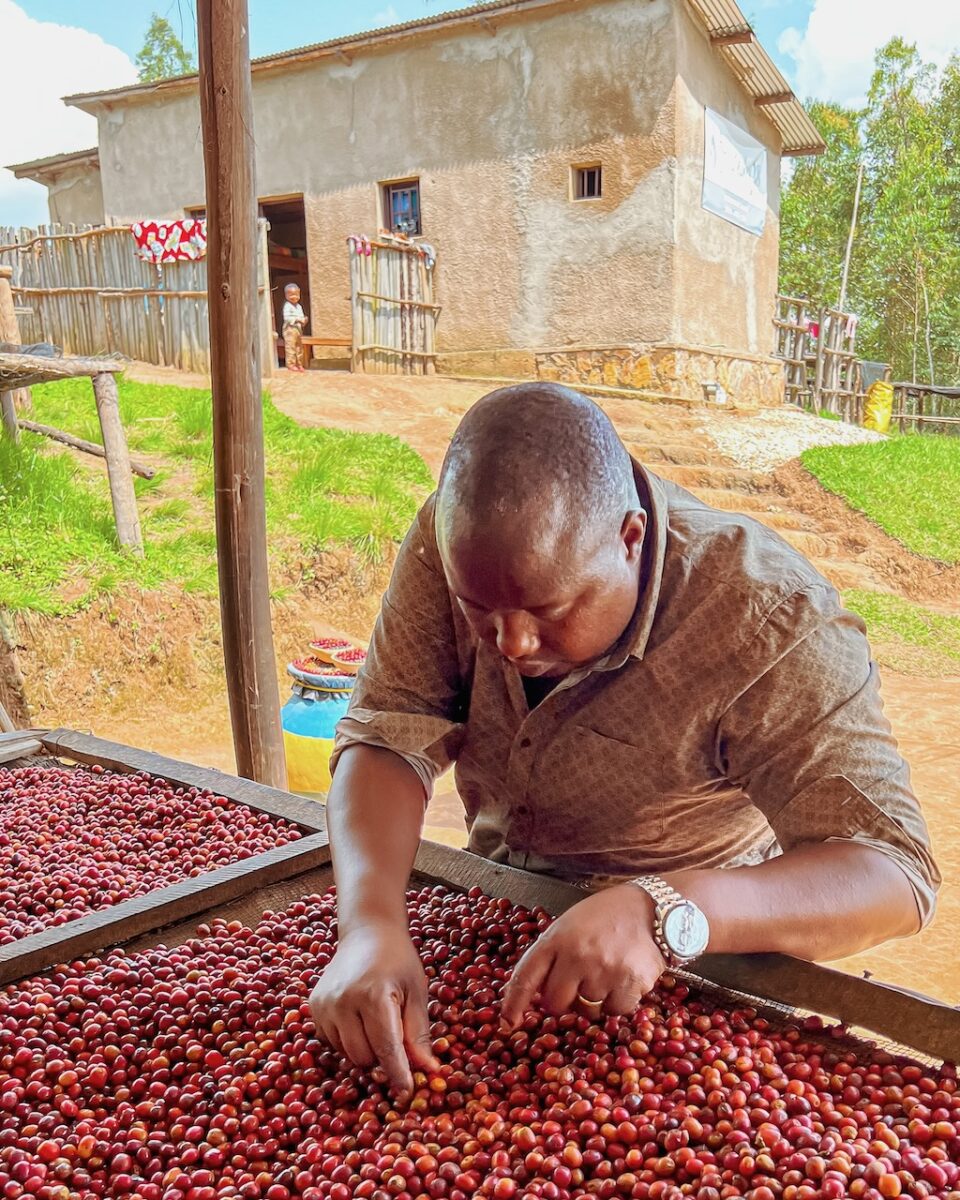

When Emmanuel says he wants to be a partner for coffee farmers 365 days a year, that’s not some pleasant-sounding catchphrase. He means every word of it, as evidenced by Baho’s various programs aimed at building closer relationships with farmers. For Baho, coffee producers are at the foundation of the business.

One such program seeks to help farmers to improve their production techniques. Employees well-versed in agricultural engineering make regular visits to farmers and suggest better cultivation methods.

Baho organizes its partner producers into small groups and appoints a leader in each. Leaders are tasked with identifying challenges faced by farmers in their group and report the issues to agricultural engineers. Baho aims to improve overall quality by finding solutions together with farmers.

Baho also runs a program to support the lives of producers. For instance, the company provides them financial assistance when they ask for help with tuition fees, health insurance costs or operating funds ahead of harvest seasons.

“We want our farmers to feel part of Baho when they work. When someone buys their coffee, we pay them an incentive like we give them a gift. That’s because they are family.”

A country of around 10 million people, Rwanda is said to have roughly 500,000 small-scale coffee farmers. They produced great coffee. But its price was kept low because the country wasn’t well-known on the international coffee market. This was a cause of poverty among farmers.

“When we sell coffee, we are not just selling coffee. We are selling the entire country of Rwanda. The share of specialty coffee in the domestic market has increased to 50%, up from 10% in around 2010. Also, more and more people are recognizing that Rwanda is an origin of high quality coffee.

I want to be among the promoters pushing this shift. Our goal is to become the first choice for every roaster and importer when they want to order specialty coffee from East Africa.”

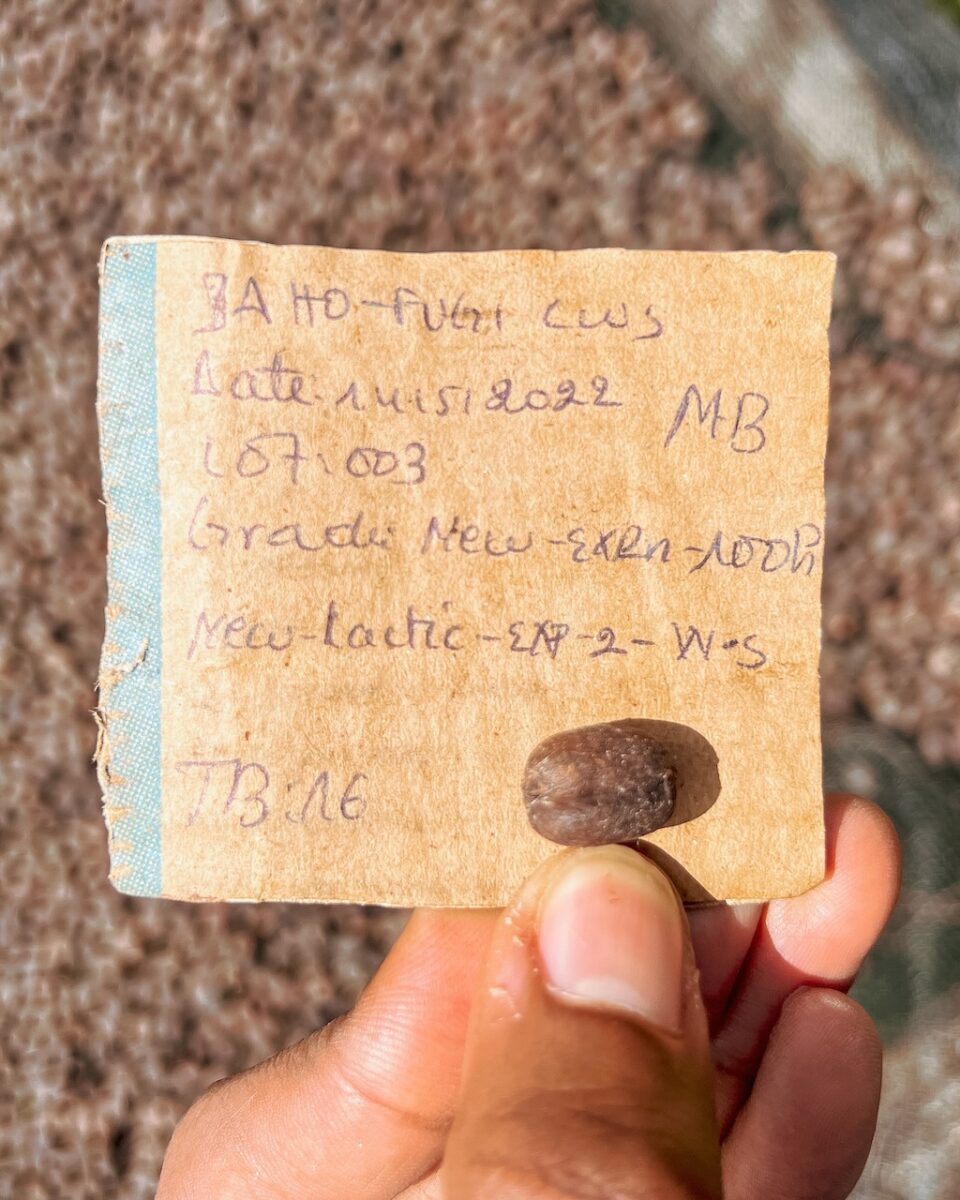

One coffee bean defect that’s common in Rwanda and its neighbors, such as Burundi and the Democratic Republic of Congo, is potato taste defect. Green beans with this defect give off a raw potato-like odor, which, when they are roasted, destroys the delicate flavors of specialty coffee.

“From harvest to export, we spare no effort in quality control. That has drastically reduced the risk of potato taste defect. We guarantee that if it ever becomes an issue, we will responsibly find a solution together.”

For the least of these

Emanuel’s coffee life began when he landed a job at a major coffee exporter after he graduated from university in 2005. Starting his career as a washing station manager, he swiftly moved up the rungs of the corporate career, earning a promotion to head of organic certification and sustainability. He went on to take charge of 37 washing stations (15 company-owned and 22 partner stations).

Emmanuel had no dissatisfaction with the job. But deep down, he was craving for something more. He was becoming aware of a gap between what he could do at the company and what he really wanted to achieve.

“Many of my family members and relatives were engaged in coffee production. So I understand the pain of the farmers. I kept asking myself how I could change their lives and make them happy. That is how I came to the idea of starting Baho.”

Emanuel resigned from the company in 2015, telling his supervisors, “I have a dream. I have to go for it.” Driven by a desire to do what he can, no matter how small, for the needy and vulnerable, he started preparing to set up his own business.

“Baho means ‘stay strong’ and ‘never give up.’ It’s an emotional word. It’s the word to cheer up your friends when they are struggling with life or people feeling miserable and looking down.”

Trials and Tribulations

Emmanuel was born in 1978 as the eldest son of a farming family. In addition to coffee, they produced bananas, cassavas, potatoes and beans. The family had five children. It wasn’t easy to provide them food and clothes, let alone pay for their school fees.

It was perhaps these circumstances that awakened a sense of mission in Emmanuel. He was the helpful one among his siblings. So they would often take advantage of his hardworking nature and have him do chores for them. But when he did, praise from his mother brought a joy like no other.

As in so many other families in Africa, Emanuel’s mother took care of everything around the house by herself. Emmanuel helped her out almost every day, their bond getting deeper and stronger. When he was tired, a pat on the back from his mother was all he needed to rejuvenate himself. There was no secret between them. She held a special place in his heart.

Poverty has a way of tearing families apart. It can bring out the worst in the most gentlemanly of a person. Emanuel loved his father. But when he saw his father laying a hand on his mother, it felt as if a part of him died. While consoling his mother, Emanuel vowed to be her biggest supporter in the future.

Then came the genocide in 1994. Around one million people were killed in an ethnic conflict between the Hutu and the Tutsi in a matter of 100 days. Among the victims were Emanuel’s parents and his youngest brother.

His heart sank to the depths of despair when he found their bodies. He tried to throw himself into a nearby river to follow his parents. But it wasn’t his time. Someone stopped him. But living as a survivor came with trials and tribulations.

In Rwandan households, the eldest son is expected to lead the family. Emmanuel had to take on that responsibility at the age of 15. He cleaned restaurants and carried heavy cargo, toiling away to provide for his siblings. What little money he had left, he spent on transport to go to school. But he couldn’t afford a school uniform, or even a soap to wash his shoes with.

After Emmanuel finished secondary education at 19, he taught at a secondary school for four years before continuing on to university. The salary was just enough to cover living expenses. But having a stable source of income felt like a dream life. When he was 23 years old, he had a house built for about 500 dollars, using money he’d made from four years of work, which paid some 25 dollars a month.

“I’ve tried to commit suicide twice in my life. I couldn’t bear the weight of responsibility as the eldest son to protect my family. I failed both times. I survived by the grace of God. I continued to struggle until I became who I am today. All this time, it was the word ‘Baho’ that kept me going.”

Living for others

Having overcome all the odds, Emmanuel’s words carry special strength. With him, the term “burning soul” isn’t a mere euphemism. He is a blaze of energy as if his soul was literally on fire.

“I always tell the farmers and my staff to never give up and be strong. I want them to be encouraged by the fact that a man who has tried to take his life twice is now running a business like this. Who would have thought that I would be interviewed by people in Japan and the US and get to travel to Europe?

I’m not afraid to talk with my staff about my history. Baho is me. I started it, and there is no one else behind me. But I can’t do anything by myself. I need farmers, I need pickers, I need my staff, I need roasters. Without them, I can’t make my ideal come true. This is a chain. Together, Baho.

So many lives were lost during the genocide. It was like Rwanda’s history ended then and there. But with the current leadership, with our government, Rwanda has become one of the safest countries in the world. Now, Rwanda is attracting the attention of overseas investors as a country with among the biggest business opportunities in the world.

Even if today is not a good day, you shouldn’t lose hope that tomorrow will be a better day. Don’t give up. This is the energy that drives Baho forward.”

Emmanuel married in 2009. Today, he lives a happy life with three children, no longer struggling to put food on the table and clothes on the backs of his loved ones. Still, he is not done yet in his pursuit of further happiness.

“I keep working hard because I know that if I work, someone else will be able to buy food and clothes, because I know that some other people can change their lives. My life isn’t just mine. I live for myself and also for others.”

Emmanuel is now distributing five million coffee seedlings to farmers for free, covering the costs with his own money. His desire is pure and pristine. He just wants to help improve the lives of farmers through coffee and make them happy.

That said, Emmanuel is a human, too. There are times when he feels like giving himself a break and taking it easy. But every time such thoughts occur to him, he remembers his mother saying, “If you don’t work hard, dogs will eat you.”

“For people in Rwanda, dogs are just animals. So when someone says dogs will eat you, it means you will become useless. I have a lot more things to achieve. I need to keep working hard.”

30 years have passed since Emmanuel lost his family to genocide and a chance to fulfill his promise to be the biggest supporter for his mother. But that regret has given him the empathy and compassion he lavishes on every coffee producer today.