Sustainability is in the heart

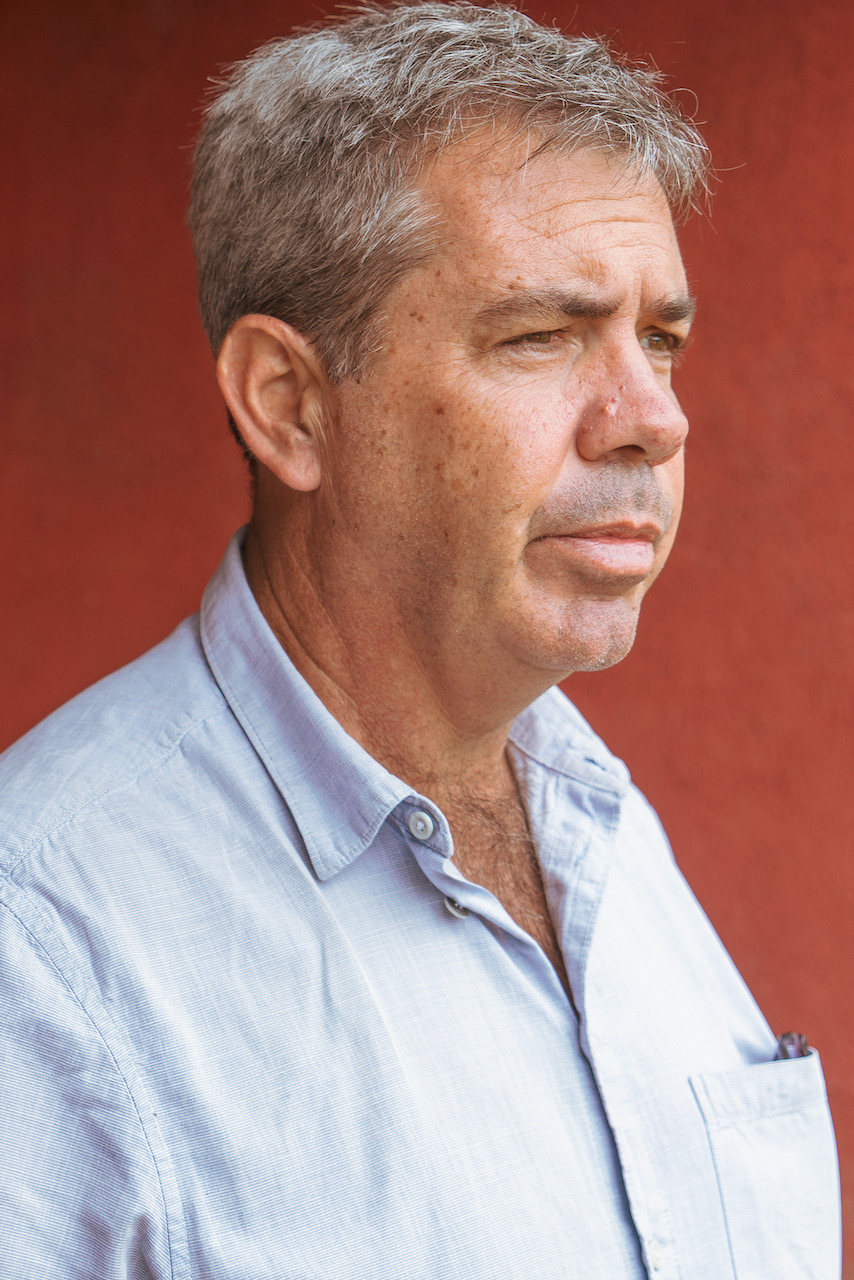

We visited Tanzania for the first time this year. After traveling in the south of Tanzania, we arrived at Kilimanjaro airport late at night and were warmly welcomed by Leon. From the moment we met him, we felt his calm and gentle nature and was a kind gentleman.

Leon’s farm, Acacia Hills, was listed as the winner of a private auction in Tanzania organized by ACE (The Alliance for Coffee Excellence). Tanzania is still in its infancy as a specialty coffee producing country, and I decided to reach out to him to learn more about the producers at the forefront of the industry.

Leon’s story embodies the history of coffee production in northern Tanzania itself, and it also vividly reflects the future of specialty coffee in Tanzania. After returning to Japan from our trip, we spoke with him online.

In the pursuit of quality

The history of coffee in northern Tanzania begins in the 19th century. Coffee trees were brought to northern Tanzania from Reunion Island near Madagascar and immigrants from Germany, the occupying country at the time, developed it into an industry.

“Most of the coffee plantations here in northern Tanzania seem to have been established around the 1920s after World War I. An old map we’ve come across, showed that about 80 German immigrant families moved here and established small coffee plantations.”

Leon’s grandparents were also immigrants who came to Tanzania from Greece around the early 1900s and made a living from coffee production. Leon is the third generation of the family. The family’s house is located on the outskirts of Arusha, near the Kilimanjaro International Airport. His grandfather and father mostly grew coffee in its surrounding plantations, but the land was not suitable for producing high quality coffee due to its low altitude. Leon learned about the concept of specialty coffee in the 2000s and started looking for lands in high altitude that could produce higher quality coffee.

“In the past, and still today, coffee produced in Tanzania is rarely consumed at home. Everything is exported, and most of it is commodity coffee. As the international price of coffee has dropped, it has become more difficult to make a living from coffee production. It was inevitable that we would switch to specialty coffee,” Leon said.

Meeting his partner

It was around this time that Leon met his current business partner, Mark Stell, at the 2005 EAFCA exhibition (currently known as AFCA). Mark is the founder of Portland Coffee Roasters in the US. Leon and Mark hit it off, and in 2007 they jointly purchased a coffee plantation on Mount Oldeani, which is now known as Acacia Hills. Leon was convinced that if Mark, who knew about roasting, and he, who knew about farming, could work together, they could create a synergy.

There were two reasons why they decided on Oldeani as their new farm land. The first was that the best Tanzanian coffee Mark had ever tasted was from Oldeani. The second reason was that Leon had heard a researcher say that the soil in Oldeani was ideal for growing coffee.

Leon rebuilt the rundown farm and began planting high quality coffee trees, including Kent, SL28, Geisha, and Pacamara. With his dedication and the wonderful natural environment, Acacia Hills grew in coffee quality and production.

The land around Acacia Hills borders the Ngorongoro Conservation Area, which is home to many wildlife including elephants, buffaloes, and many more. When we visited, we saw many trees that were knocked down by animals. “They are amazing animals for marketing your coffee,” Leon said, but managing to keep them out was the biggest challenge he faced.

Cupping at Crater

”The first harvest was not of good quality or quantity, and Mark bought all the coffee. However, we couldn’t continue to rely on him. So we started working with neighboring coffee growers and invited international roasters to participate in what we call ‘Cupping at the Crater’.”

The cupping event, named after the Ngorongoro Crater (the caldera where the volcano erupted), was held at Leon’s Cupping Lab in Oldeani. The atmosphere was intimate and friendly, but the result of this event was significant enough to rewrite the history of specialty coffee in Tanzania. Tanzania has a strong reputation for commodity coffee, but this event brought the attention of the market and proved that it was now producing excellent micro lots.

This cupping event eventually evolved into an official auction in 2020 with the cooperation of ACE. The auction was attended by famous roasters from all over the world, and the coffee producers around Mount Oldeani were highly evaluated and talked about.

Acacia Hills was able to raise their coffee quality with Leon’s dedication to producing higher quality coffee, and also because of the roasting experiences and the influence of his business partner Mark. Even if you make a good coffee, if you don’t have the ability to get it out to the world, it will never see the light of day.

Leon says, “In the future, we would like to encourage producers in other areas to participate in the auction. There are still great coffees in Tanzania that should be known to the world.

”What is the one single thing that would change your lives”

“What is the one single thing that would change your lives?” was the question Leon and his colleagues often asked the staff working on the farm.

“And invariably the first answer we were always given was: Education and water. Actually I’d put water before education because, in theory, most areas of Tanzania are covered by some sort of government school. When we first took over these farms, there were women, and men, and old men, and donkeys and carts, they were walking. We estimated there were people walking four kilometers to fill up 20L containers of water, from high up on our farm, because our farm used to comber in an open furrow (an open stream to the farm). ”

So Leon, together with Mark and an Australian roaster, developed the water infrastructure in Oldeani. They installed a water supply system on two farms and set up a pipeline that uses gravity to transport water to a water tank in the village. When Leon and his wife visited the farm in the beginning, the U.S. government (USAID) had been distributing maize, the staple diet of Tanzanians, to the villagers. Having witnessed this, Leon must have a first-hand knowledge of what the community really needs.

Besides these social projects, Leon’s constant success in Oldeani has had a positive impact on the people around him.

“I think that employment, and all the wages that have been paid out over the years, have changed the community. I can see the amount of shops, little shops, that are below our farm now. Where there is money, business follows, more business follows. So, I have seen a change in the people, yes, definitely.”

The entire region of Oldeani can be changed by the presence of one man who can implement business ideas where the people involved in coffee production will be happy, and the people around them will be happy.

“I think if our model could be sort of replicated by other farms, or other cooperatives, or things of that nature, it would help the Tanzanian coffee industry, which could ultimately help the people involved in the coffee industry.”

For the specialty coffee industry, where sustainability is the toughest issue, Leon’s practice will be a very valuable teaching tool.

Tanzania’s Charm

Although Leon focuses on coffee production now, he once had a career in pharmacy in the UK. When he was young, he never thought he would take over the family business.

Leon decided to move to Tanzania when Leon and his wife Eileen, who was also in the same pharmaceutical field, began to think about starting a family. “In her 20’s, if I’d said, ‘Should we move to the moon ?’ She’d have said, ‘Yes. No problem.’ Because we were young married people, everything was possible.” On returning to Tanzania Leon mentions, “it was a lovely place to bring up children. We had our extended family, my father, mother, my sisters, brothers… everybody’s here, so we have a big network, and we all support each other.

Tanzania has very nice weather, most of the year. Very friendly people. You know the Tanzanians are incredible. They just have a soft nature, very kind people. Sometimes they’re not the most ambitious people, but they’ve got a very kind nature, and that’s infectious.

People work hard but it’s not all about work, you can take vacations and spend time with your family and friends. It’s a great place to start a family, and more and more young people, like my nieces and nephews, are choosing to live in Tanzania after working for a while in Europe. After all, they have Tanzanian blood in their veins.

Also, there’s a good work-life balance in Tanzania. People work hard, but it’s not everything. So there is time for holidays, and time to see your friends and family. For example, I have many nieces and nephews who have been educated and tried their first few jobs in the UK, and other countries, and a lot of them end up back in Tanzania because Tanzania is in their blood.”

There is a relaxed atmosphere in Tanzania. I felt as if the majestic nature was not rejecting people, but accepting them. One of the buyers I met on my trip told me, “Tanzania is the most comfortable coffee producing country.” I truly understood what that meant.

About the future

What is Leon’s vision for the future?

“Our ultimate goal is to be here forever. The only way to do that is to produce quality coffee and find customers who appreciate it. That’s why we are committed to quality.”

The Acacia Hills farm blends in beautifully with the ridge of Mount Oldeani. Leon would occasionally get out of the car and point to the mountain ridge and explain, “We’re going to plant Geisha on that land. The Acacia trees, which look like large umbrellas, are also serving as shade trees.” I could feel Leon’s passion for this work from the way he spoke and the seriousness with which he talked with Mr. Picker.

“The specialty coffee industry in Tanzania is very exciting and is constantly growing. I heard on a podcast that young people from Colombia and Brazil have left city life behind and moved to the highlands to grow coffee. When I hear stories like this, it reminds me of the people we used to be. As I always say, as long as I don’t run out of energy and motivation, I want to keep doing things that really excite me. I think that’s what makes a business sustainable and makes it possible to support workers and small producers.”

Sustainability is in the heart. I love this human way of thinking to follow the emotions that arise naturally, not out of a sense of duty or logic.

The night he showed us around the farm, we had dinner with Leon and talked about various ideas such as, “Why don’t we add more Acacia trees to the farm? It would provide shade and make the picker’s work a little easier” and “why don’t we build a dry mill in the town of Karatu where small producers can bring their coffee?” The conversation was very lively and lasted until late at night. I am looking forward to working with Leon and sharing such dreams. It’s this kind of feeling that will be the driving force for sustainability.