Providing Equal Opportunity through the Vessel of Coffee

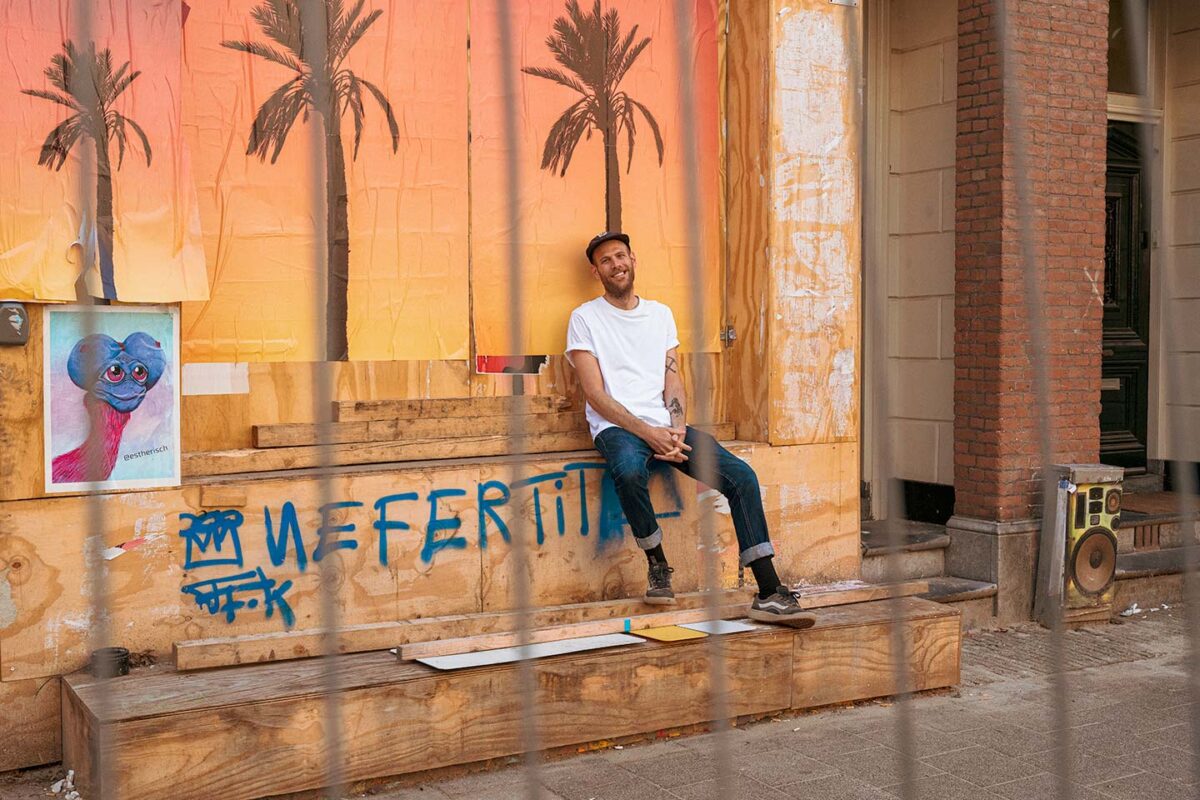

Ernest Andrews joined TYPICA’s Europe team as a community manager in January 2022. A native of South Africa, he began his career as a helicopter pilot before entering the coffee industry as a barista when he was 20 years old. In the more than 10 years since, he’s been involved in coffee across different roles, including quality controller and roaster.

Ernest used to run a roastery cafe, determined to become a bridge between producer and consumer through direct trade of specialty coffee. For someone with that background, TYPICA seemed like a stage where he might have another chance to make his dream come true.

After about 10 months and much introspection and soul-searching, now Ernest is envisioning a brighter future.

Building a bridge takes more than one person

It was September 2, 2019, and 30-year-old Ernest was at the pinnacle of his life. The day after he married his wife, they opened a roastery cafe. It was something of a culmination of his career.

The cafe was a standout in Cape Town, South Africa, where offerings of high-quality specialty coffee, directly sourced from producers, were far and few between. People in the country predominantly consume instant coffee, in the first place. The market share of specialty coffee is less than 1%. Even drip coffee – a type of coffee you make by grinding the beans and brewing them – has yet to be popular.

Still, Ernest and his wife’s venture got off to a good start. Shortly after opening, their roastery was nominated as South Africa’s “Best New Roastery.” On top of that, they won a contract to serve coffee at the world’s biggest yacht race during the competition’s first ever landing in the country.

When they served coffee at its trial events, feedback was exceptionally good – so good that the owner of the organizers even asked them to serve coffee at the event’s other series around the world.

They rejoiced. It was a moment that a decade of their hard work finally paid off. In front of them was a stairwell guaranteed to lead to a future full of hopes, or so they thought.

But fate has a way of reversing fortunes. In December 2019, two weeks after Ernest signed that contract, he received a text from the organizers saying, “A new virus has been found in Italy,” where the event’s head office was located. This meant they might have to cancel the race in Cape Town.

“This can’t happen to us now,” Ernest thought, upset and frustrated. Then came the ultimatum. The race was called off.

In response to mass outbreaks of the novel coronavirus, the South African government declared a state of national disaster in March 2020. Ernest and his wife did everything they could to keep their business afloat, even amid a lockdown and travel restrictions. But despite their best effort to find a way forward, they hit a dead end. Once again, Ernest had to look for a career change.

But the company he started working at wasn’t dealing with specialty coffee, it didn’t seem to be an ideal place to chase his dream of realizing a sustainable future. But then again, he was past 30 years old, near the peak of his career. That meant he wasn’t necessarily an ideal candidate, either, for businesses looking to hire. Being at a loss where to go, Ernest was grappling with a midlife crisis. With no end of the pandemic in sight, unnerving uncertainty started to take hold in his mind.

As if to fight back waves of anxiety, Ernest applied for 12 job openings in one night, but not at random. He only picked businesses where he thought his previous experiences would be useful. Their locations, however, were all over the map. From Europe to the United States to Australia to Japan, his search encompassed the entire globe, especially since working in South Africa was no longer on the table.

One of the 12 applications Ernest sent was to TYPICA, a Amsterdam-based venture of two Japanese co-founders. It took him just a quick peek at their website to understand the company’s philosophy and vision. His heart beating with hope and joy, Ernest spent a few hours rewriting his CV to tailor it to TYPICA. An opportunity he had long coveted was now in front of him, to a certain degree.

“To be honest, I wasn’t really interested in becoming a community manager, which was what TYPICA was looking for. I saw the role as a sales position selling the beans to roasters. I didn’t really see myself in that job.”

But Ernest quickly came to terms with it because TYPICA’s “values and vision align with mine,” he said, “So I thought, if I can get my foot in the door and deliver results, I can grow within the company to make the change I want to see.”

Ernest has one memorable episode after joining TYPICA. He is a friend of Rusatira Emanuel, the founder of Baho Coffee in Rwanda. Thanks to Ernest’s introduction, TYPICA was able to offer Emmanuel’s coffee on its platform, and then marked a record high sales for the Europe base.

“The volume was so much more than I could ever buy when I was running a roastery cafe in South Africa. I always wanted to help Emmanuel grow as a curator and empower all the small farmers in Rwanda. But just by having him as part of the TYPICA platform, I was able to see him succeed on a much bigger scale. It was a very big highlight for me that truly showed my joining TYPICA has made an impact on the entire community of people that Emmanuel works with.

Even before knowing TYPICA, my intention was to become a bridge between producers and roasters. But after that experience, I had to make peace that I couldn’t build this bridge on my own. Through the support of the entire team, TYPICA helped me to make this small dream I had a reality.”

Searching for True Equality

Helping those in need has always been at the core of Ernest’s heart. It is a desire he inherited from his father, who is a dentist, and his mother, who is a nurse.

Ernest grew up in the small village of Eshowe in South Africa’s east. With a population of about 10,000, the village was home to many Zulus, an ethnic group long discriminated against merely for their dark skin.

Since 1948, South Africa was under apartheid, racial segregation under which the dominant white people – which comprised roughly 20% of the country’s population – discriminated against non-whites and classified people strictly along the racial lines.

Places of residence were determined by race. Authorities forcibly removed Black people from their houses and resettled them in the least hospitable living environments. Non-white people were denied suffrage. All public facilities, including restaurants, trains, and toilets, were separated into “For white” and “For non-white.” The segregation policy is considered a lesson for the world to learn from, a chapter of human history never to be repeated.

Apartheid ended in 1994, when Nelson Mandela became the first Black South African President. The country transitioned to democracy, and non-white people gained access to education. Society was moving toward the light at the end of the tunnel. Back then, Ernest was in his early childhood.

But things don’t change that easily, Ernest says. “People were still from a disadvantaged background. They didn’t have the income to buy a better car and better food, or to live in a bigger house.”

It was under these circumstances that Ernest’s father started a dentist practice in the village. Being aware of South Africa’s structural problems, he built two separate waiting rooms with different entrances, one for the affluent and one for those less privileged.

To make the distinction visible, the room for the affluent had nicer chairs than in the other room, but both rooms had water, coffee, and tea. As a professional, Ernest’s father provided the same level of service to whoever crossed the door, whether it was bankers and lawyers or janitors and farm workers.

One thing that he did differentiate was treatment fees. He charged lower-income patients only around one-fifth of the amount he billed the higher-income group, who often had insurance coverage – a decision he made to help others, in exchange for his own income.

“In today’s context, you may think everyone should be treated equally and charged the same rate. But my father understood where those people came from and what kind of life they lived. So making that distinction was the fair way for him. He was giving everyone equal access to health care. My goal is to be like my father.”

Whenever Ernest and his brother needed treatment, they were told to wait in whichever room that was less busy. Being a son of a dentist didn’t give Ernest any more special treatment than for other patients.

In a way, Ernest’s mother contrasted starkly from his father, who was making a tangible impact on people’s lives. If there was water on the floor, she would “lie down on her stomach and let you walk over her back so you don’t get your feet wet,” Ernest recalls.

“When I was young, we went on a family camping trip through Africa for two months. Every day, my mother woke up at 4AM and started packing, making snacks, and filling in all the documents for border control. And every evening, she would help everyone set up their tents and start cooking before she started doing anything for herself – all this with a smile on her face. She worked herself to the bone every day to make sure that we had the best holiday.”

Privilege Comes with Responsibility

If Ernest ever had concerns about working as a community manager, his early days at TYPICA proved his worry wasn’t entirely unfounded. Ernest was struggling, caught between a role that he knew wasn’t best suited for him and the expectations placed upon him. He was vacillating, torn between the conflicting pressures of selling the green beans to roasters and maintaining relationships with them.

“The biggest reason I wasn’t able to deliver results was the difference between my ideas of achieving sustainability and TYPICA’s. Before I joined TYPICA, I thought intermediaries shouldn’t make profit when connecting roasters and producers. I never thought of sustainability as something that can come from business.

But Masa (*Masashi Goto, chief representative of TYPICA) showed me that without making profit, there is no sustainability in the true sense of the word. It made a lot of sense because if you look at Patagonia, they have been in business for 50 years and still growing under the mission statement, “We are in business to save our home planet.”

Masa points out Ernest needed to “unlearn,” casting aside all the things he’d learned before.

“Masa often talks about the ‘ultimate dimension.’ It can be difficult for everyone to understand and execute that mindset. But how we can get there is clear. It is to never doubt the idea of a better future. Without fail, it’ll be a reality. We have the goals of having 33% of all Arabica coffee traded through TYPICA and of lifting 200,000 small farmers out of poverty. These are not just aspirations we are working toward, but a fact that’s going to happen.

I believe so especially after what we saw with Baho Coffee. It showed that producers are willing to participate, and so are roasters to pay a better price. When both sides put their faith in TYPICA, it translated into a result we’ve never seen before. And that is proof our vision is going to be a reality.”

At 19 years old, Ernest became a helicopter pilot. He wanted to save lives, even if it meant putting his own in danger – a compassionate heart he inherited from his mother. When he combines that with the practical, business savvy of his father, TYPICA is the place where he can shine.

“My goal at TYPICA is to give all producers the opportunity to have the education and knowledge to understand how to sell their coffee and make a living. My role in life is to teach people in less fortunate countries and regions that they have the opportunity to break out of their current situation.

If I can increase the amount of specialty coffee traded through TYPICA, I’m able to alleviate the pains of people suffering from poverty and starvation. For me, coffee is the vessel to provide equal opportunity.

I think the only way we can succeed in life is for the privileged people to sacrifice a little to give opportunity to as many people as possible. Because if we don’t, the future is bleak. I want to do everything I can to avoid that.”

Text: Tatsuya Nakamichi