Journal

#4 El Salvador

From the terror of war to a blueprint for peace: The resilience of El Salvador

El Salvador may be less than half the size of Costa Rica, but it is home to one of the largest populations in Central America with 6.5 million people. Living in such close quarters has fostered a sense of sincerity, resilience, and a strong work ethic within the Salvadorian people. And while most Latin American countries are known for their carefree and easygoing nature, El Salvador stands out for its calm demeanor and unshakeable loyalty. This personality is also reflected in the unique flavor of their coffee. However, there is another aspect to this loyalty. When it comes to war, Salvadorians are fiercely committed to their cause. In the civil war that lasted until 1992, left-wing guerillas rebelled against the right-wing government, and anyone considered an enemy was indiscriminately killed. In Nicaragua, tolerance was shown to enemies during the civil war, but in El Salvador, torture and brutal killings defined the conflict. In Spanish, El Salvador means “the Savior,” yet the country could not save itself from the horrors of civil war. Today, though memories of the civil war still haunt, peace has finally been restored. El Salvador is moving forward with its innate resilience and determination to rebuild the country.

An era of fear and civil war

In the mid-1980s, when El Salvador was in the midst of civil war, I traveled to the country every two months. The 30-minute drive from the airport was a matter of life and death as highways were contested territory for both the guerillas and government soldiers. Just before we left the airport, the taxi driver turned to me and said, “Keep your head down below the window. At least until we arrive.” The car window had even been taped to prevent the glass shattering from gunshots.

In the heart of the capital, around 20 fully-armed soldiers patrolled the streets, communicating via radio. Military trucks equipped with automatic weapons carried armed soldiers through the city, guns pointed at the citizens. Police cars patrolled in pairs, guns protruding from their windows. Above it all flew military helicopters, their propellers beating the air, hovering in a constant state of alert. The driver gestured toward the scene. “Just another day in paradise.”

Almost daily, the newspapers featured images of abandoned corpses, their bodies scarred from torture and faces bearing knife wounds. This was the work of the death squads – assassination groups formed by far-right paramilitary groups. Wanting to see the frontline firsthand, I visited the Ministry of Defense and spoke to a government army lieutenant to find out more about the situation. I asked him where the worst of the fighting was taking place. He walked over to the map on the wall and pointed at multiple locations indicating almost everywhere. I asked when the fighting usually happens. “24 hours a day,” was his answer. At the end of our conversation, he gave me a letter of introduction to hand to the commander of the eastern front. As we parted ways he laughed lightly and said, “Try not to get yourself killed and maybe we can meet again!” Three months later, I spotted his photo in the newspaper. Another assassinated victim.

Yet amidst this chaos, there were still glimpses of normal life. The malls in the city center sold electronic goods imported from Japan. The markets downtown were overflowing with fresh fruit and vegetables. Unlike the civil war in Nicaragua, the government was supported by the US and aid continued to pour in, ensuring a steady supply of goods despite the conflict. Local women dressed in high fashion and shopped as if they were in New York. The distant boom of occasional explosions had become nothing more than background noise, something people had been forced to become accustomed to in exchange for trying to scrape back a sense of normality.

The coffee war

The history of coffee in El Salvador is intertwined with the country’s social and political struggles, providing insight into how it found itself in this state. After gaining independence from Spain, the Regalado and Sol families, along with other wealthy landowners, consolidated their power and became the central force in government. Known as the “Catorce Familias” or “Fourteen Families,” this landed elite took political and economic control of the country. Though the actual number of families was around 250, they were still a minority ruling class wielding power over the impoverished majority.

The wealth gap in El Salvador was extreme. The wealthy lived in barbed-wire fenced mansions, patrolled by armed guards. The poor lived in overcrowded slums, visible from beyond the walls of the rich. The disparity within the country was staggering. And behind all this amassed wealth was the coffee industry.

At the end of the 19th century, the Fourteen Families pushed the indigenous people from their land and passed laws to force them to work on coffee plantations. The people rebelled, but were quickly suppressed by the newly formed national guard. In El Salvador, military force was not only used against foreign countries, but as a tool to control its own citizens. Through fear and military intimidation, the country became distorted, with 2% of the population controlling 60% of the land.

As time passed, the military gradually gained more power, and in 1931, established a military dictatorship. The following year, when farmers armed with hoes and machetes rebelled, the government ordered for them all to be massacred. More than 30,000 indigenous people were killed. The military dictatorship persisted for 50 years, as the landed aristocracy and military allied themselves and created a climate of fear that permeated society.

The Fourteen Families used the power of the military to force impoverished farmers to work on their plantations for next to nothing, reaping the benefits of their labor. Under the threat of violence, the poor were left with no voice or power and had no choice but to endure. Yet, despite this, the farmers remained loyal to their work ethic, resulting in the production of good quality coffee. By the 1970s, despite its small size, El Salvador had become the third-largest coffee producer in the world, producing more than double its current yield and carving out a dominant position in the global market.

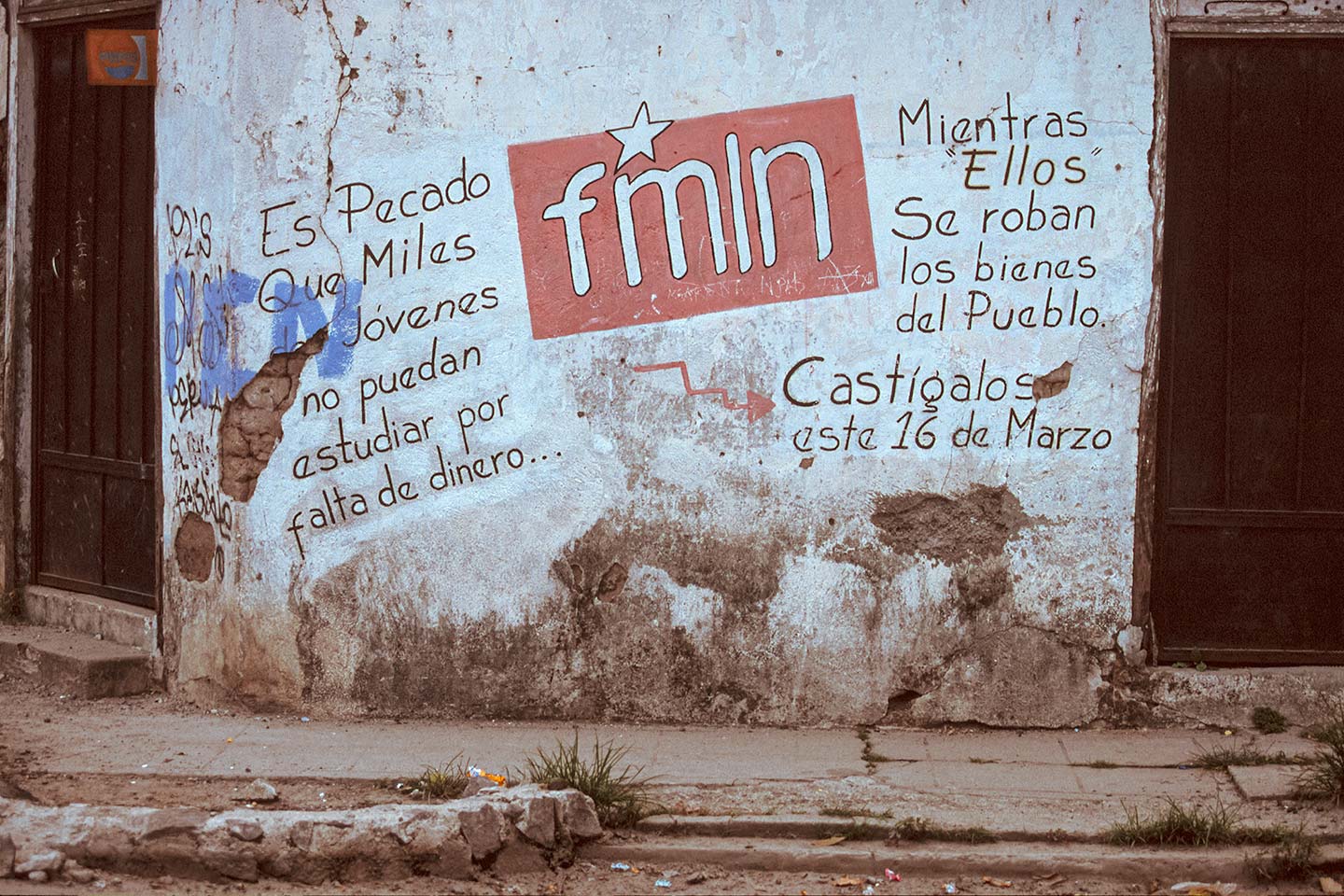

However, the oppressed majority was nearing breaking point. In 1980, a death-squad assassination of a Catholic archbishop, a vocal supporter of the people, sparked the beginning of an armed conflict waged by the left-wing guerilla group, Farabundo Marti National Liberation Front (FMLN). This was the catalyst that plunged El Salvador into civil war.

The FMLN launched their first major offensive in a key coffee collection area, targeting Santa Ana, the second-largest city. Their objective was to halt the shipment of coffee and deal a severe blow to the economy, while also undermining the government’s international reputation. The government garrison in the town rebelled, killing their commander, and joined the guerillas. The guerillas had gained the upper hand and a revolution seemed imminent. But the US stepped in to bolster the government with aid, tipping the balance of power and leading the country into a bloody conflict.

When I visited in 1984, the conflict had escalated into what became known as the Coffee War. The guerillas attacked the largest coffee factory in the country, setting fire to 3000 bags of export produce, and attacking transport trucks. Total damages were estimated at around $20 million. If the attacks continued, the government knew there was a risk that the whole economy could collapse, highlighting just how much the country depended on the coffee industry.

End of civil war and a blueprint for peace

The civil war ended in 1992, following the signing of a peace agreement mediated by Costa Rica and the United Nations. The war had raged for over ten years and both sides had reached a point of exhaustion, with the death of the right-wing colonel who had led the death squads being another significant turning point. The war had resulted in the death of 75,000 people and the displacement of one million refugees.

It was remarkable how smooth the transition to peace was. Generally, a peace agreement does not mean the end to conflict and resentment. But in El Salvador, after peace was restored things quickly returned to normal, which speaks volumes for the peaceful nature of the people.

The left-wing guerillas transitioned into a political party with the same name, and one of the guerilla commanders, Salvador Sánchez, became a member of parliament. Originally a primary school teacher, he joined the teacher’s union and eventually became involved in guerilla activities in his village. He was one of the five commanders of the guerilla forces and continued to fight in the mountains for 12 years. In 2000, he was elected to parliament, and in 2014, at the age of 69, he became the president of El Salvador, serving until 2019.

While some guerillas advocated for continued fighting, the majority of the people desired peace. The prevailing consensus was to let bygones be bygones and focus on rebuilding the country. The police force was dismantled and replaced by a citizen police force made up of former guerilla soldiers. Over eight months, the government gradually reduced the size of its military to balance with the guerilla forces. “Our peace process has been the most successful yet. It is a blueprint for the world,” Sánchez said with unabashed pride.

The civil war ended in 1992, following the signing of a peace agreement mediated by Costa Rica and the United Nations. The war had raged for over ten years and both sides had reached a point of exhaustion, with the death of the right-wing colonel who had led the death squads being another significant turning point. The war had resulted in the death of 75,000 people and the displacement of one million refugees.

It was remarkable how smooth the transition to peace was. Generally, a peace agreement does not mean the end to conflict and resentment. But in El Salvador, after peace was restored things quickly returned to normal, which speaks volumes for the peaceful nature of the people.

The left-wing guerillas transitioned into a political party with the same name, and one of the guerilla commanders, Salvador Sánchez, became a member of parliament. Originally a primary school teacher, he joined the teacher’s union and eventually became involved in guerilla activities in his village. He was one of the five commanders of the guerilla forces and continued to fight in the mountains for 12 years. In 2000, he was elected to parliament, and in 2014, at the age of 69, he became the president of El Salvador, serving until 2019.

While some guerillas advocated for continued fighting, the majority of the people desired peace. The prevailing consensus was to let bygones be bygones and focus on rebuilding the country. The police force was dismantled and replaced by a citizen police force made up of former guerilla soldiers. Over eight months, the government gradually reduced the size of its military to balance with the guerilla forces. “Our peace process has been the most successful yet. It is a blueprint for the world,” Sánchez said with unabashed pride.

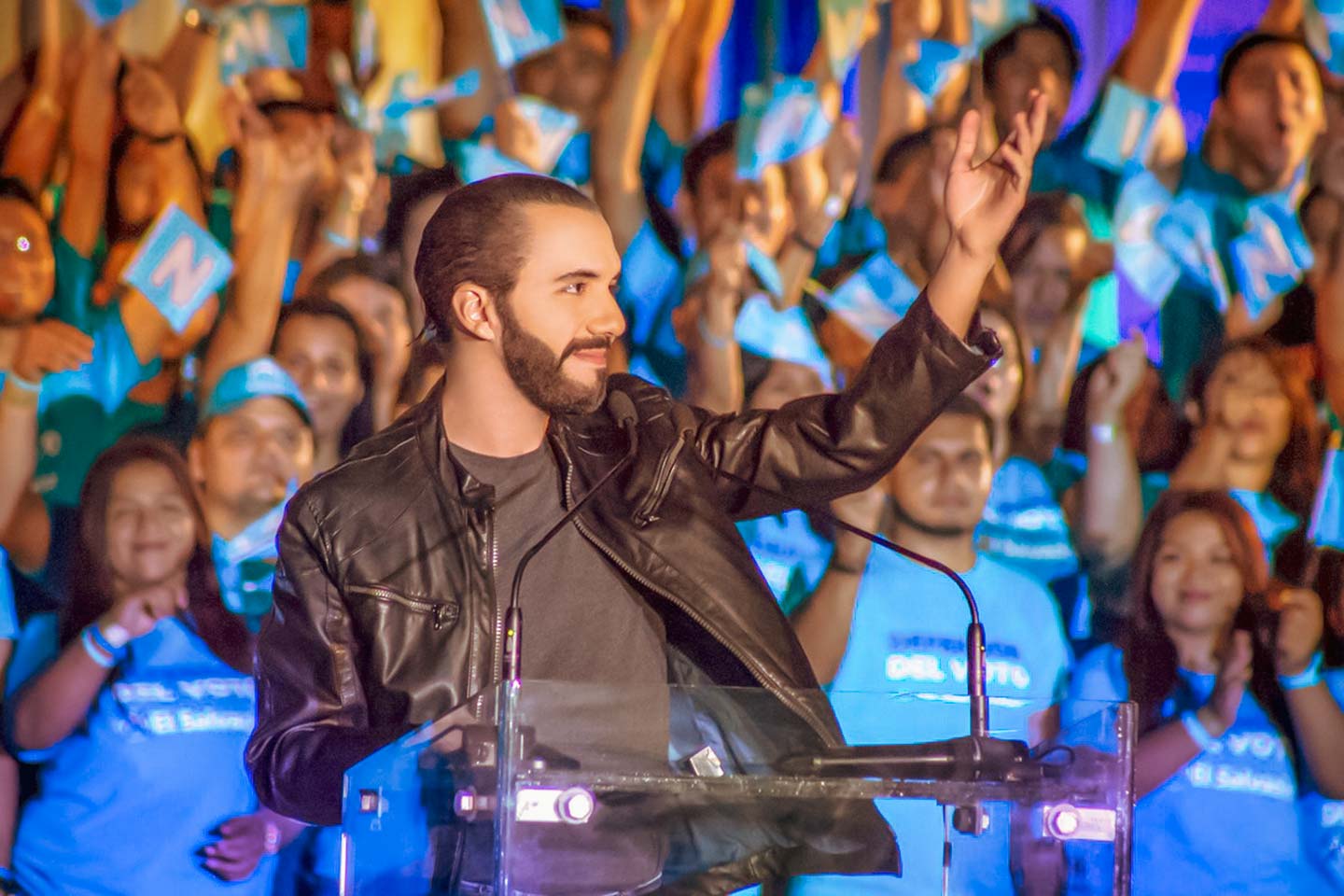

The country continued to move toward democratization. In 2009, FMLN won the election and took power. They may not have won the war, but the election allowed them to achieve their objective. In 2019, Nayib Armando Bukele Ortez, a former FMLN member and a center-right candidate, became the youngest president in history at the age of 38. A young entrepreneur, he owns a Yamaha Motor dealership in El Salvador, and Japan was where he paid his first presidential visit after taking office.

Despite the decline in coffee production due to the prolonged civil war, the agricultural economy still relies heavily on coffee, with over 25,000 families making their livelihood from it. Now, the government is focusing on exporting specialty coffee in an effort to regain its former status as the Kingdom of Coffee.

Invisible scars of war

While much progress has been made, not everything is running smoothly. Trials for human rights violations during the civil war are still ongoing, and division lingers in the hearts of the people. The economy is also taking time to recover, and many Salvadorians continue to travel to the US for work.

Shortly after the end of the civil war, I visited El Salvador with twenty other Japanese to see a village that was once a guerilla stronghold. The people who had fled during the conflict had returned. The scars left by the government’s airstrikes were still there, as were the landmines.

In the village stood seven or eight wood and brick structures. It was the village school, built by hand. I saw this as a positive sign, that the government was placing a priority on education as it worked to rebuild the country. The school not only welcomed children, but also adults who had been unable to study due to the war or poverty. There was also a rehabilitation center where people who had lost their limbs due to bombing or landmines underwent therapy to achieve functional recovery. Anibal, a 23-year-old former guerilla soldier, told me that three of his nine siblings were killed by government soldiers, and four joined the guerilla forces. “My whole childhood, I’ve only known war. I don’t know anything about working in society,” he sighed.

Graciela de Garcia, a 40-year-old nun, is helping farmers improve their lives. She still bears scars from being tortured by the government army. “In the past, death, from starvation or massacre, was the only way for people to find peace.” But now we can find peace in life. So I want to find a way to escape poverty,” she told me. Her plan centers on coffee production. The village has enough workers to grow coffee, and she is looking for an organization to help them export. It’s a plan that I or anyone would be glad to lend their support to.

A simple meeting hall, constructed from four thin wooden poles and a corrugated roof, was the location for our welcome party. Young people played the guitar and sang, while the villagers performed a play. The play depicted a farmer and his son at home, raided by two government soldiers who accused the father of being a guerilla before killing him. The surviving son taught himself law and studied to become a judge. In court, the two soldiers were brought before the son, and he revealed his identity, before delivering the verdict according to the rule of law. The message of the play was that justice, not violence, is the answer.

Outside the meeting hall, armed soldiers and police officers stood guard as a deterrent to raids by former government soldiers who had lost their jobs after the war. Suddenly, the lights went out and everything was pitch black. I immediately hit the floor. During the civil war, government soldiers would cut the power and shoot through the door, and this was a reflex reaction. brought on by my experience of the war. When the lights came back on, I looked over to see the villages in the same position as me, but the Japanese guests had not moved, and looked slightly bemused.

I’d only visited the country a few times, and yet it had left an indelible mark on me. I could not begin to comprehend the depth of the psychological scars carried by the villagers. The rehabilitation center is treating around 150 children suffering from mental disorders, who often run around in fear at night. I hope that one day they are freed from the sadness and fear left by the war, and find stability in their lives and minds. If high-quality coffee production could be a means to achieving that, then there is nothing else I could wish for more.

Despite the fear of the civil war, and the sadness of losing loved ones, the resilient Salvadorian coffee producers continue to give their all in their work. When you see El Salvador origin coffee, please take a calm and peaceful moment to remember their struggles, and appreciate the flavor.

*Full-width Photo: These El Salvadoran FMLN guerrillas demobilized in Chalatenango, for the Peace Accords with the government in 1992. / scottmontreal