Journal

#6

Brewed by the Canal: Panama, the Country that Launched Geisha to Prominence

Stretching as far as the eye can see, the panoramic view is nothing but the ocean. The scenery from the deck of a cruise ship sailing across the vast sea is breathtaking. Especially in the early morning, witnessing the sunrise emerge from the horizon is a truly exceptional experience. In the tropical waters of the Caribbean Sea, the sun exerts its powerful presence, radiating a scorching heat as it ascends. It's as if standing right beside a blazing stove, feeling your entire body engulfed in warmth. Sipping coffee under the radiant light invigorates your spirit. Heading south in the Caribbean Sea towards Panama, I arrive at the birthplace of a legendary coffee known as the pinnacle of specialty coffee, Esmeralda Special.

God in a cup

Located at the isthmus connecting North and South America, Panama may appear as a longitudinally elongated country. However, its true geographical form resembles a winding S-shape, curving from east to west. At its center lies the Panama Canal, while the western boundary of the central mountain range is marked by the impressive Baru Volcano, soaring to an altitude of 3,474 meters. It proudly claims the title of Panama’s highest peak. It is on the eastern slopes of this volcano that the celebrated coffee region of Boquete unfolds, known for its exceptional coffee production.

The year 2004 marked the rise to prominence of the Peterson father and son, proprietors of the renowned Esmeralda Estate situated in the Jaramillo district of the Boquete region. It was during this time that their Geisha variety coffee, entered in the esteemed Best of Panama competition, clinched the championship title and fetched an extraordinary price of $21 per pound. The value further soared to $170 by 2010, and in 2013, a small lot of natural process coffee achieved a remarkable price of $350.25.

The year that became legendary was 2006, during a tasting competition. A well-known industry figure from the United States described the experience by saying, “In that moment of tasting, I saw the face of a god in their cup,” and this phrase quickly traveled across the globe. Esmeralda, in Spanish, means “emerald.” The gemstone word for emerald is “happiness, good fortune.” It indeed brought happiness to Panama.

Price Peterson, the father, was a scholar who had been a professor of neurochemistry at a university in the United States. Upon retiring from his position as a bank executive, he chose to settle in a secluded area of the Boquete region, which he had acquired as his retirement abode. There, he began cultivating vegetables and delving into dairy farming. In 1996, he purchased a new farm and ventured into coffee cultivation together with his son, Daniel, who had recently graduated from university.

To begin with, they explored their surroundings, and that’s when they stumbled upon an eccentric wild coffee tree. It was a slender, elongated Geisha variety, which, despite its unimpressive appearance and low yield, exhibited remarkable resistance to both coffee rust and strong winds. Demonstrating the true spirit of a researcher, they planted this tree in diverse locations for observation. However, it was the daring decision to nurture it on a windswept, steep slope at an elevation of 1800m—where other trees would falter—that bore astonishingly delicious coffee beans.

From Gesha to Geisha

The roots of the Geisha variety trace back to an English diplomat who, in 1931, encountered coffee seeds during his collection of wild coffee samples from the Gesha region in southwestern Ethiopia. These seeds were subsequently dispatched to Africa and various countries in Central and South America. Eventually, in the 1950s, they found their way to Costa Rica’s Coffee Research Institute, where they were planted. Along the journey, this variety acquired the label “Geisha,” a name that would forever cement its identity.

During the 1960s, employees of the Panamanian Ministry of Agriculture, on a quest for coffee trees resistant to leaf rust, sourced the seeds from Costa Rica and distributed them among nearby farms. Sadly, the grown trees yielded meager harvests and lacked flavor, leading them to be neglected and left to wild growth. Had it not been for the fortuitous encounter by the Peterson father and son, these trees might have remained abandoned and overlooked.

By the way, even in the small towns of Costa Rica, you can find cafes specializing in serving Geisha coffee. In our first installment, we featured Brumas del Zurquí, a coffee farm in Costa Rica that offers Geisha coffee packaged in bags adorned with illustrations of Japanese geishas. It’s a delightful display of Latin humor and business acumen in this region.

It is the indigenous Ngöbe community who undertakes the task of harvesting coffee cherries on the farms located in the Boquete region. These individuals have endured land appropriation and discrimination by the government. However, their tenacity prevailed in the 1980s when they pursued legal action, reclaiming their land rights and establishing an autonomous zone. Immigrants from the United States have contributed their knowledge of the market economy, fostering a cooperative relationship aimed at producing high-quality coffee.

Panama is also home to the Cuna tribe, an indigenous community famous for their colorful craftworks known as “Mola.” This art form involves layering multiple vividly dyed fabrics and skillfully revealing the lower layers to create intricate designs of birds and flowers. In the early 20th century, the Kuna people rose up in a mass rebellion against the government, securing their right to self-governance. This vibrant land is inhabited by a resilient community whose artistic expression and vitality are shaped by the tropical sun.

Rudolf Peterson, the father of Price Peterson, who acquired land in the enchanting Boquete region, was born in Sweden in Northern Europe. It was the European immigrants who initially introduced coffee cultivation to Panama when they arrived to construct the Panama Canal. Following the canal’s completion in 1914, a significant number of them decided to make Panama their permanent home instead of returning to their homelands. Europeans, particularly those from Northern Europe, have a deep appreciation for coffee. Seeking refuge from the scorching canal zone, they sought solace in the cool and picturesque Boquete region, dedicating themselves to coffee cultivation. A Norwegian engineer even established a coffee processing facility in Boquete. Thus, it can be said that the canal acted as a magnet, drawing the coffee industry to this thriving area.

Sipping coffee on world’s shortest transcontinental railway

With the canal, coffee shipments to both Europe and Asia become incredibly convenient. Since coffee is primarily exported for profit, transportation costs can be a significant factor. Even if production costs are low, the prices can escalate significantly by the time the coffee reaches consumers. By reducing transportation expenses, businesses can keep the selling prices in check and enjoy favorable commercial advantages.

Panama has also thrived in the banking sector, offering favorable conditions for financial transactions. During my assignment as a correspondent in Brazil, I faced a challenging issue. Funds transferred from Japan could only be withdrawn in the local currency by Brazilian banks. When conducting interviews throughout Central and South America, having cash in US dollars became essential. The sole solution was to travel to a bank in Panama to withdraw funds in dollars. These various reasons attract people from different regions of Central and South America to visit Panama.

It is common for Japanese ships to be registered under the flag of Panama, despite being Japanese-owned. Panama offers favorable taxation policies for maritime vessels, allowing shipowners to minimize their tax burden. Moreover, Panama-flagged ships enjoy discounted rates for traversing the Panama Canal. As a result, some individuals establish shell companies in Panama solely for the purpose of registering their ships under that company’s name, serving as a form of tax avoidance.

On the Caribbean side of the canal, there is a town called Colón, named after Christopher Columbus. It serves as a free trade zone, where a sprawling section of the port, enclosed by fences, showcases a wide array of electrical products imported from Japan, Europe, and the United States.

The construction of this town was undertaken by the United States. In the midst of the California Gold Rush in 1850, as Americans flocked to the region in search of their fortunes, the United States established the Panama Canal Railway to facilitate their journey. Stretching over a length of 77 km, it stands as the world’s shortest transcontinental railway. The railway was founded in 1855, with Colon serving as its starting point on the Caribbean coast. Tragically, the Chinese laborers brought in for the railway’s construction fell victim to malaria and scorching heat, resulting in the loss of approximately 9,000 lives over a five-year period. This era was marked by the saying, “a death for every sleeper.”

It was in 1984 when I took my first ride on this train, and the small station lacked ticket gates, with the tracks partially engulfed by weeds. Operating with a five-car formation pulled by a diesel locomotive, it offered five daily departures. The total number of passengers, including myself, amounted to a mere 30 individuals. As we journeyed forward, the tall weeds outside would cascade into the interior through the open windows. Passing by seven stations, we arrived at a station on the Pacific coast in 1 hour and 46 minutes.

Upon revisiting in 2010, I was amazed to witness the remarkable transformation of both the train carriages and the station itself. Primarily used for cargo transport, the train now accommodated only one round trip for passengers per day. The passenger cars had been completely refurbished, with the addition of an observation car where passengers could savor complimentary coffee while admiring the scenic landscapes. Furthermore, the travel time had been reduced to just one hour.

Conflict with US

Panama City, located on the Pacific coast, is a bustling metropolis with towering skyscrapers. During my visit in 1999, I witnessed the citizens engaging in protests. These demonstrations were a response to the US military invasion of Panama that had taken place a decade earlier.

In December 1989, the US military launched an attack on Panama City with a force of over 50,000 troops. Even soldiers from the US Southern Command stationed in the Canal Zone were mobilized, resulting in the complete annihilation of the Panamanian Defense Forces through overwhelming military superiority. The invasion was justified by the alleged involvement of General Manuel Antonio Noriega Moreno in drug trafficking. Noriega was captured and taken to the United States, where he received a guilty verdict and was incarcerated. He died in 2017 at the age of 83. Nevertheless, the act of invading another country and forcibly capturing its leader is an incredibly aggressive action. The invasion resulted in a significant loss of life on the Panamanian side.

The United States not only constructed a canal in Panama but also played a role in establishing the nation of Panama itself. Prior to this, Panama was a part of Colombia in South America. Driven by their ambition to secure control over the canal, the United States orchestrated the separation of Panama from Colombia, seizing dominion over the newly formed country. Through diplomatic pressure, they imposed a treaty upon the Panamanian government, granting the United States permanent territorial rights over a 5-mile (approximately 8 km) strip on both sides of the canal.

An influential figure, General Omar Efraín Torrijos Herrera, endeavored to have the entire canal zone returned to Panama. He successfully engaged in negotiations with then US President Jimmy Carter, resulting in the successful return of the canal. Following General Torrijos’ untimely demise in a mysterious plane accident, General Noriega assumed power. Speculations emerged, suggesting a possible collusion between the United States and General Noriega in the assassination of General Torrijos.

Visiting Panama during the Noriega era was a saddening experience. Panama lacked anything to be proud of. The country heavily relied on imported goods, thanks to the income generated from the canal, which hindered the growth of domestic industries. Panama didn’t have its own currency; instead, they used US dollar bills. Barbed wire fences encircled the canal and US military bases, effectively keeping Panamanian citizens out. On top of the mountain, overseeing the canal, the majestic Panamanian flag flew high, symbolizing a modest display of sovereignty.

However, by the end of 1999, the canal and its surrounding areas were returned to Panama. The US military completed its full withdrawal. Concerns arose about accidents under Panamanian management of the canal, but the accident rate decreased compared to the US era. Finally, a sense of joy returned to the hearts of the Panamanian people.

Sailing across the canal

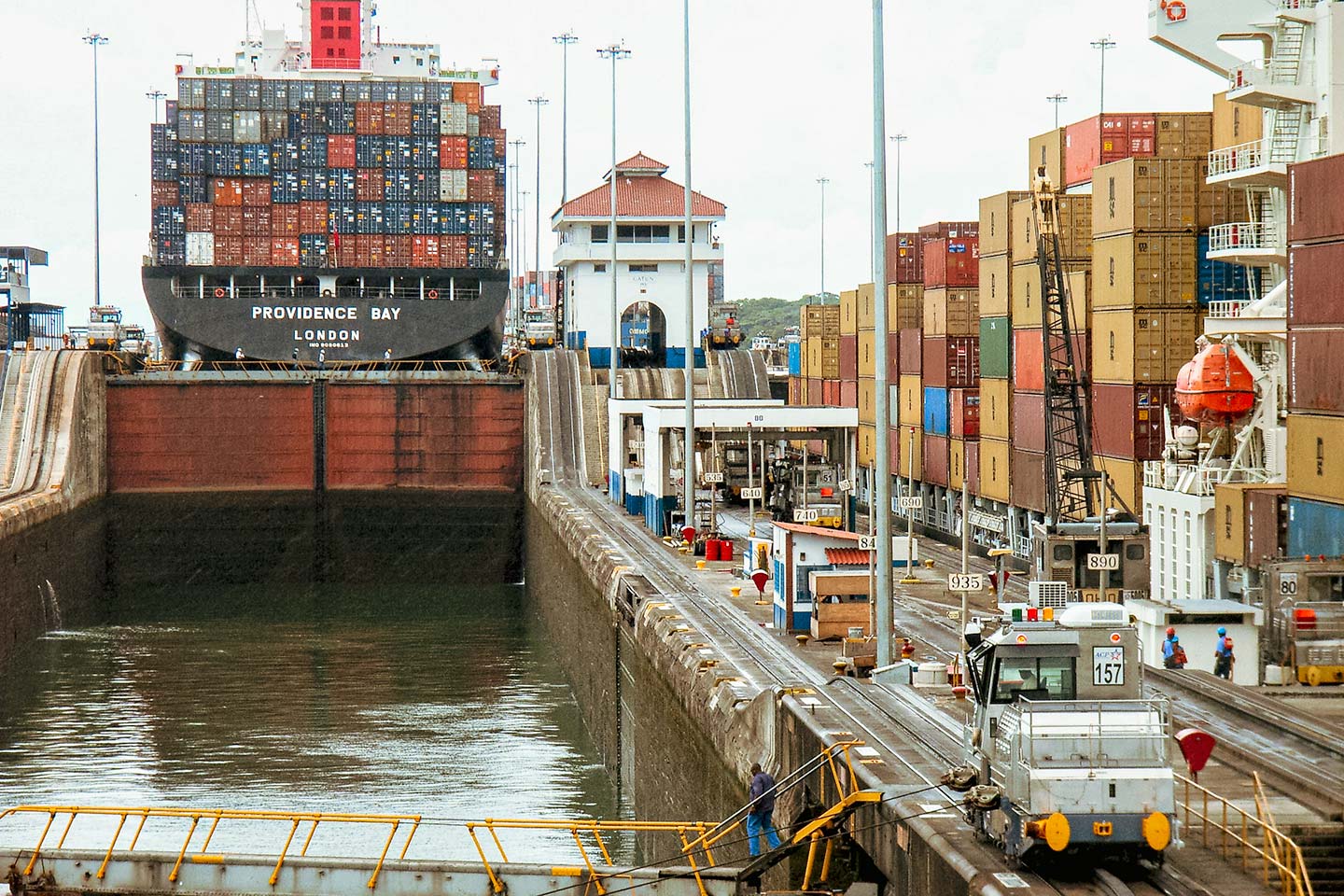

Let’s embark on a ship once again and cross the Panama Canal. The canal is bustling with a multitude of ships, so we wait offshore. Finally, in the early hours of the morning, we receive permission to proceed. The ship approaches the canal entrance, and there looms a massive red and black iron gate, standing 25 meters tall. The two doors, each about 20 meters wide and nearly 2 meters thick, open slowly on the other side, revealing a straight waterway ahead.

On both sides of the waterway, four locomotives stand aligned on rails. We throw a rope from the ship and secure it to the locomotives. With a signal akin to that of a tram, the locomotives begin to move. The width of the waterway is 33.5 meters, just enough to accommodate the ship’s width. Carefully, the locomotives pull the ship forward, ensuring it doesn’t collide with the waterway walls.

After around 5 minutes of progress, the ship comes to a stop. The iron doors ahead are closed, and the iron gate we passed through earlier shuts behind us. The ship finds itself enclosed within a 305-meter-long chamber. Water rushes in through approximately 100 holes in the walls and floor of the waterway. As the water fills up, the ship rapidly ascends. It feels like riding in an elevator, with the ship soaring to a height equivalent to a 3-story building, about 9 meters, in just 8 minutes. At this point, the iron doors ahead open, and once again, the locomotives pull the ship forward to the next chamber.

After repeating this cycle three times, gradually ascending to an altitude of 26 meters above sea level, a vast lake comes into view. This lake is a man-made reservoir, created by damming the river. The echoes of howler monkeys’ calls reverberate through the surrounding forest. Observing from the branches of towering trees in the tropical rainforest are sloths, lazily hanging in suspension.

Once again, a gate comes into view ahead. Descending this time, we go through another three stages. As we pass through the canal, we continue our journey, gazing at the panoramic view of Panama City on both sides. Suddenly, a colossal arched steel bridge, the Bridge of the Americas, spanning 1.7 kilometers, appears right before us. Passing under the bridge, we are greeted by an unobstructed sight: the vast expanse of the Pacific Ocean, extending as far as the eye can see.

The journey through the canal lasted for a total of nine hours. After staying on the deck throughout, my skin was exposed to the scorching sun, resulting in marks that surpassed mere sunburns, and they didn’t fade for the next two years.

Evening has arrived. The sun descends into the Pacific, casting its farewell. Along the horizon, I witness the spectacle of a sunset. A grand, intensely red orb, akin to a ripe persimmon, gracefully slips below the sea’s surface, adorning the sky with a golden hue of twilight. Sipping coffee while gazing at the evening sky brings a profound sense of peace to the soul. Immersed in the wistfulness of the journey, I bask in the glory of the star-studded sky above.